A monolith of brutalist design is facing an uncertain future. A familiar story. We have seen it many times before. This time it’s Milan’s iconic San Siro Stadium.

Completed in 1926 the stadium has been home to hundreds of events throughout the years, hosting games in both the 1936 and 1900 football World CUP. Modified throughout its lifespan the stadium has increased its capacity, from the original 35,000 spectators, to suit the larger crowds. Since 1947 both Inter Milan and AC Milan have shared the 75,000 seat stadium.

I was travelling with a couple of football fans and along with the recent news of the stadiums proposed demolition and sale of the area surrounding, we decided to head west from the city centre and take a look.

The stadium sat out in the open and being the middle of the day with no events on, the area was quiet. The grand scale of the structure was vast. Not being a football fan I have visited very little stadiums and when I have, they have of course, been to admire the architecture. San Siro was different.

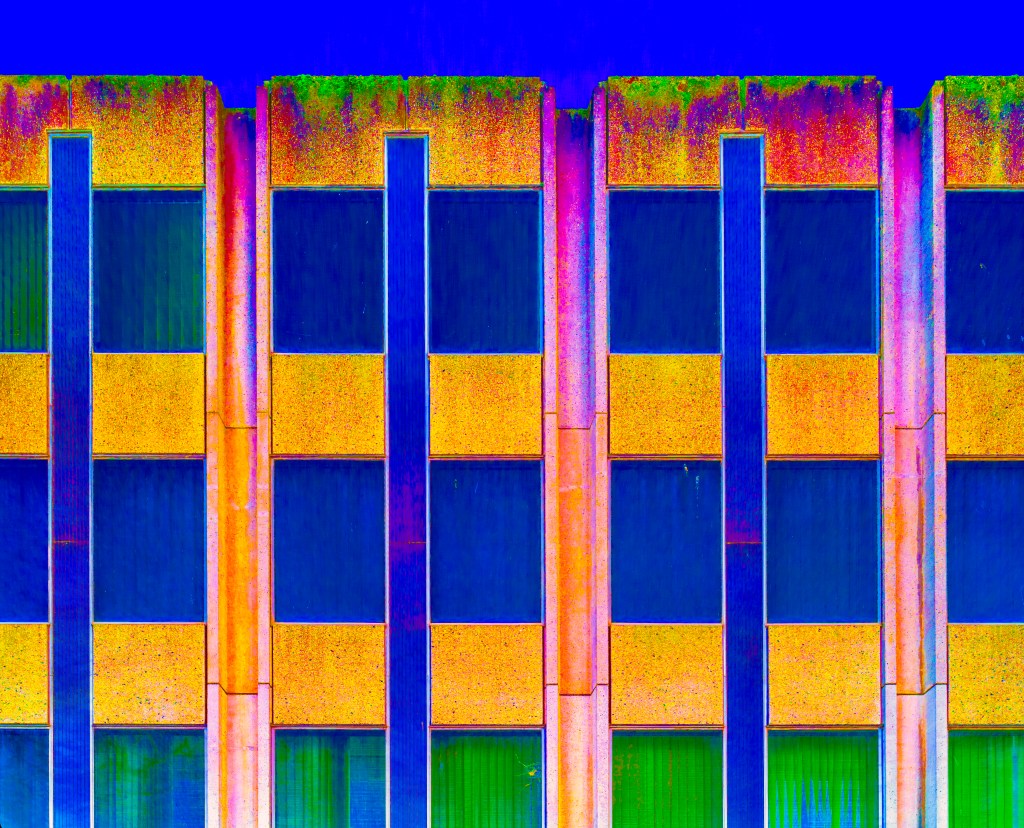

From the outside I was surprised how it looked, considering how old it was the building condition was remarkable. Over the years the stadium has had several renovations, the last being in preparations for the 1990 World Cup. It was tall too. The levels continue to go up and up. It must be quite a walk down the circular ramps that corkscrew on the buildings exterior, also providing support for the upper levels and roof.

It would have been great to see the inside of the stadium but a tour of the grounds was on the pricey side. Walking around the outside would have to do. The openness of the design allowed for great viewing, but I was drawn to the corners and the red details on the roof.

Currently plans are moving forward with a new stadium. After the sale last year a new design is due to be finalised this year, with a prospective completion date of 2031. What will happen with San Siro is still unclear. The new stadium will be on land surrounding San Siro, leaving the possibility of saving a section of the stadium which would then become a museum.

Though the condition of the stadium has deteriorated, and UEFA has excluded it from the plans for Euro 2032 due to outdated facilities, its capacity is still higher than the planned replacement. Without a new design in place we cannot compare the architecture but it will have large boots to fill. My only hope is that it at least tries.

After one hundred years of service this may be the appropriate time to tap out. Pass the torch to a modern, state of the art stadium that can carry the legacy into the future. It’s final swan song, hosting the opening ceremony for the 2026 Winter Olympic Games. Over that time it has left its mark, a large impression, that won’t be forgotten even if nothing physically remains.

Further reading:

It’s interesting that this isn’t the first time the Winter Olympics and Brutalism have crossed paths – Tallinn and the 1980 Moscow Olympics

BBC – Demolition of Iconic San Siro Stadium Confirmed

The interior is worth seeing and after visiting I doubted my decision not to take advantage of the opportunity.